Brain's Blog

|

As an academic who studies social media and how Black people self-express, it would be an understatement to say that Twitter has been an extremely influential online space in both the amplification of Black voices and the call for justice in communities. Scholars like Andre Brock (2020) and Meredith Clark (2014) have noted specifically that “Black Twitter” is a network of culturally connected communicators using the platform to draw attention to issues of concern to black communities. In my own research, I have found that Black Twitter is a great example of how Black youth and young adults self-express and utilize media tools to perform civic engagement, social activism, or even just to be funny and have a safe space for themselves.

It’s a subculture that requires high contextual information, an appreciation for the experiences and practices of Black people and ongoing engagement with the conversations regarding them. Whether it is comedic responses to Jill Scott doing a risqué performance that simulates fellatio or Kanye West getting critiqued for wearing a “White Lives Matter” t-shirt, Black Twitter builds connection through both serious and light-hearted cultural conversations that might otherwise go unnoticed in mainstream media. I often say that Black Twitter is like the Black dorm at a predominantly white institution (PWI) – It has its own experiences, practices and discourse that support Black unity, but it operates and is sanctioned by a larger institution that is not necessarily structured to the best interests of its minority community members. Though often regarded for its ability to provide a sense of belonging via comic relief, Black Twitter has played a significant role in driving conversations around more serious matters impacting Black communities. This was clearly seen in Ferguson, MO when many prominent Black community organizers, thought leaders and entertainers sparked a national dialog after the murder of Michael Brown and series of actions that many believed to be re-imagining of the Civil Rights Movement in America (Jackson & Foucault-Welles, 2015). Beyond advocating for justice in incidents where law enforcement has wrongfully murdered a Black person, Black Twitter has also helped to highlight issues of Black women, college students and Black queer communities. For example, Twitter was a major resource in the amplifying the voices of Black trans women through the hashtag #Girlslikeus, which was started after the wrongful imprisonment of CeCe McDonald for self-defense during an assault. Similarly, #MeToo is a movement started by Tarana Burke that has spawned a large amount of attention, bringing awareness toward the rampant yet unreported sexual assault of Black women. In tracing another example of young Black people using #hashtags to change the culture of formal institutions, Clarence Wardell (2014) examined the 2013 #BBUM campaign undertaken by Black students at the University of Michigan hoping to address what they perceived as a racially hostile campus environment. Twitter was not created with Black people in mind. This has been determined not only from scholars and researchers (e.g., Benjamin, 2019; Marwick, 2013), but it’s also been communicated to me by technologists who were there at its inception. That said, it is miraculous how Black Twitter has provided us with imaginaries for the possibility of democratizing public discourse through social media platforms. Technology provides creative solutions for the problems of Black people when Black people can render themselves legible in technologies. So, if we’re thinking from a utopian point of view, we can simply look at Black Twitter as being a valuable case study on the possibilities of how Blackness should be developed into technology rather than after thoughts. However, in 2023, the pessimist in me believes it is also safe to say that Black Twitter is no longer the vehicle it once was and hasn’t been relevant for Black teens in some time. Many in the millennial Black intelligentsia are upset that Twitter has continually changed its platform in ways that inhibit Black voices to be amplified in the ways that they were before. To that end, the first few months of Elon Musk’s ownership of Twitter have been rocky. In the words of the great Christopher Wallace, they want that ‘old thing back.’ Even so, substantive cultural conversations (Outrage over the shooting of Tyre Nichols, for example) are continuing to be held on the platform and allow Black people to be communal and communicate messages outside the control of the white gaze. That said, I don’t believe Elon Musk owning Twitter is in and of itself, the problem. The problem is that researchers, tech designers, and policymakers that are feverishly seeking to figure out how to better prevent the spread of hate speech within algorithms (see Noble, 2018) and to positively harness social media for corporate accountability (Pacelli and Heese, 2022), haven’t figured out how to center their work towards the needs of Black people. The real problem is that Black Twitter doesn’t have any infrastructure to be iterated on and many Black thought leaders on Twitter may be forced to rebuild their audiences in ways that they may not know how to yet. The real problem is Black Twitter is dead and people who are Twitter famous can’t let it go. However, I also don’t believe that today’s Black youth want to express themselves the way my generation did in 2010. Our notions of social norms, privacy, and what constitutes entertaining content are different now. Enabled by digital technology, Black folk (and other minorities) have new opportunities to create and broadcast knowledge. This shouldn’t be deemed in a utopian way either, but lessons learned from Black Twitter can provide a blueprint for newer platforms to intentionally provide a continuous stream of information from the Black perspective to Black people who desire to consume it. In that sense, Elon Musk might be doing Black people a favor by undervaluing Black Twitter. What I’m arguing here is that the creativity of Black youth and young adults is such that if they don’t have Twitter as an outlet to hold cultural conversations or building community, they’ll be okay. History has shown that Black folk will always be inventive in digital communication and finding a sense of belonging on social media platforms. Black folk will find a way to continue to be dynamically Black on the internet. I dream of the day I can say the next version of the community built on Blackness is better than Black Twitter because it will be built by Black people. In that sense, maybe it isn’t Black Twitter but a Black-owned version of Twitter that stands to come out of this moment in time. Now that would truly be dope… Finally, for all of the commentary that has highlighted how millennial, funny and college educated Black people utilized Twitter to organize and give one another a safe space to communicate, I believe that there are still other Black youth communities that sit outside of the respectability politics of that faction that have been excluded as even being considered a part of Black Twitter’s nucleus. Some of the most beautiful cultural organizing I have seen was happening among gang-affiliated youth on the Southside of Chicago memorializing slain teenager Odee Perry by creating a hashtag naming his housing project #oblock in his memory. Through those in Chicago’s Hip-Hop community, this hashtag has been used to traverse terrain and unify young people who were once rivals to make calls to stop senseless violence in their communities. In thinking about democratization via digital tools and its affordances for Black people, I believe this is the kind of unorthodox case study that needs to be examined to accomplish digital democracy. And for all the joking and roasting common on Black Twitter that results in trending topics, the comedic sharing being done are not always entirely “politically correct” and still contain their share of misogyny, homophobia, colorism, classism, and ableism. Though I benefit from Black Twitter’s tendency to amplify Black intelligentsia, future spaces that seek to extend on the phenomena of Black Twitter will need better support for those people who sit at the margins of the margins. Besides creating spaces for diversity teams and hiring more Black technologists, I guess what I’m hoping is that Twitter and other social media platforms look at Black intersectionality as a strength rather than a weakness and see these communities not as just power users but those with the potential to be powerful users. This means doing more than inviting Black people to the “dance for digital citizenship” but also giving them the aux cord to somewhat influence the outcome of their experiences on social media References:Benjamin, R. (2019). Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code. New York: Polity Books. Brock Jr, A. (2020). Distributed blackness: African-American Cybercultures. New York City: New York University Press. Clark, M. D. (2014). To tweet our own cause: A mixed-methods study of the online phenomenon” Black Twitter” (Doctoral dissertation, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill). Heese, J. and Pacelli, J. (forthcoming). The Monitoring Role of Social Media (December 20, 2022).Review of Accounting Studies. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4278696 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4278696 Jackson, S. J., & Foucault Welles, B. (2016). # Ferguson is everywhere: Initiators in emerging counterpublic networks. Information, Communication & Society, 19(3), 397-418. Marwick, A. E. (2013). Status update: Celebrity, publicity, and branding in the social media age. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. Noble, S. U. (2018). Algorithms of oppression. In Algorithms of oppression. New York: New York University Press. Wardell, C. (2014). BBUM and new media blacktivism. U. Gasser, R. Faris, & R. Heacock, Internet monitor, 111-112. tagged with 29.07, black culture, Black Twitter, Digital Citizenship, social justice, Volume 29

1 Comment

By Jabari M. Evans

In Issa Rae’s newly produced HBO show, Rap Sh!t, the series follows Shawna Clark (Aida Osman) and her estranged friend Mia Knight (KaMillion) who team up to form a rap group in hopes of making it big. In addition to pursuing her dreams as an aspiring rapper, Mia is a single mom who is shown working multiple jobs to maintain her lifestyle and care for her daughter, Melissa. In the show’s pilot, for example, Mia is shown working as a makeup artist by day and an OnlyFans creator by night. She is also revealed (through contextual knowledge) to be both an Instagram influencer and a former exotic dancer. She’s depicted as the inspiration behind the group’s branding and image, despite lacking much lyrical ability. This becomes evident during one scene in the pilot where Shawna tells Mia she won’t resort to exposing her body online to gain more visibility from industry gatekeepers, and she tells Mia that her “art is not for the male gaze.” Mia asks in response, “What’s so wrong with having people look at you?” Further adding, “Is that what you think is going on? We’re in the middle of a Bad Bitch Renaissance… Loosen up, have some fun, just see where it goes.” Hypermasculinity expressed by Black male artists in Hip-Hop is largely tied to both the need for Black men to express their frustrations and exert power within a culture they helped create. Conversely, this hypermasculinity has also been commodified as a means to sell Blackness in a way that appeals to the demands of a largely middle-class White audience. I believe this particular vignette from the show is important because though fictional, it makes the larger claim that there’s a new revolution occurring in Hip-Hop culture, one in which women artists have readily embraced their erotic capital as a liberatory part of their artist identity. In the last 5-10 years, this brand of rap music has dominated the Billboard charts and propelled artists like Nicki Minaj, Mulatto, City Girls, Saweetie, Kash Doll, Megan thee Stallion, and Cardi B to great prominence and massive financial success. Though Hip-Hop music created by Black men has generally perpetuated misogynoir (racist and misogynistic images of Black women), Black women’s intervention into Hip Hop is not new. Black women artists like Roxanne Shante, MC Lyte, Queen Latifah, Salt N Pepa, and Yo-Yo helped establish feminist tradition within Hip-Hop that should be acknowledged as a predecessor to the more sexually charged work of Lil Kim, Missy Elliott, Trina and Foxy Brown. Though rap music is amid what Rae’s show calls a “bad bitch renaissance,” Hip-Hop culture has also never had a period with which sexualized bodies of Black women weren’t seen as a tool for the promotion in song lyrics or music videos (Miller-Young, 2014; Sharpley-Whiting, 2007). This can particularly be seen in rap’s connection to strip club culture, where dancers routinely seek monetary and cultural capital within their social networks, (while rap music also entertains the audience). From the 1993 Sir Mix-A-Lot song “Baby Got Back” to the 1998 Ice Cube-directed movie The Players Club and 2001’s Snoop Dogg’s AVN Award-winning pornographic film Doggystyle, images and logics of strip club culture have been a mainstay within the rap music industry. These logics rely on the eroticism of Black women, particularly with most popular music videos and rap lyrics focused on ‘the booty’ as the most valuable representation of Black femininity, to harvest attention and sell products. Though highly visible in the world of Hip-Hop, Black women are historically more exploited and cannot assert agency within the economies that exploit them (Brooks, 2010). To that end, sociologist Mireille Miller-Young (2014) proposed the “Ho Theory” as an analysis for labor tactics and identity formations for Black illicit erotic performances. Ho Theory purports that there’s a link between mass media, hip-hop culture, and pornography that can be traced to a long history of Black women’s bodies being associated with criminality and degradation. Miller-Young writes that Black women have been seen as “a figure of moral corruption, social deviance, and economic drain, especially in the field of Hip-Hop influenced sexual media” (p. 146). In using women’s bodies as a form of promotion tool (via music videos, live concerts and album covers), feminist media scholar Moya Bailey argues Hip-Hop has historically conditioned its audience that Black women are only good for sexual encounters. In the realm of social media entertainment, I would argue that this erotic capital is only being made more immersive, dynamic, and ubiquitous. However, it could also be argued that the cultural capital of today’s female rappers seems to be at a tipping point, willfully and joyfully using erotic capital for sustainable celebrity. The level of agency Black women are afforded through performance of sexual dances (e.g., twerking on TikTok or YouTube), queer activism, public messages of body positivity, and digital forms of sex work (e.g., OnlyFans) are no longer as marginal as earlier Hip-Hop scholars led the general public to believe (Brown, 2019; Halladay, 2020; Khong, 2020). In fact, in the digital era of music, one could argue that female rap artists use sexual appeal as a badge of emotional freedom rather than a marker of oppression. This trend has presented an opportunity for these women to self-commodify, curate, and monetize this process in ways that has led some scholars to believe digital sex work serves as a form of empowerment (Miller-Young, 2010). For example, upstart rapper Rubi Rose publicly claimed she made over $100,000 in 48 hours on OnlyFans. Popular from appearing in music videos and being a social media personality with over 1 million Instagram followers, Rose charged $49.49 for a monthly subscription to her content and has claimed to have made $1M on the platform since 2020. She has signed a record deal with music mogul L.A. Reid’s Hitco Entertainment. Therefore, it is possible to comprehend the OnlyFans content creation of female rappers like Rose as “hope labor” (Stuart, 2020), volunteer work that is the assumed precursor to more mainstream relational labor, serving as a training ground for building an ongoing and eventually (hopefully) lucrative audience (Duguay, 2019). Though many of today’s emergent women rappers have restructured the terms of which their sexual performances are distributed, circulated, and paid for, they also still reaffirm the need for women artists to rely on stereotypical tropes associated with the “video hoe” or the “vixen” in order to gain visibility. Essentially, while many argue they serve to empower their personal pathways to digital clout and financial success, they also reproduce the status quo of hypersexualized representations of Black female bodies in mass media. Some might even describe this as a familiar repackaging of Black feminism for heterosexual male audiences. That said, many questions remain about the sustainability of the current reign of female rap in the contemporary industry. As I write this piece, I’m still wrestling with what to make of the ways that Hip-Hop culture has continually thrived on the back of Black women’s bodies and erotic capital. Does it matter if women rappers cleanse their material of stripper culture while the male rappers continue to profit from it? On one hand, I believe these women rap artists are finally getting the reparations they’ve been owed from the music industry. On the other, I truly wonder if it makes a difference if female rappers are going platinum or owning their sexual content if their messages are becoming more dynamic in reproducing the negative stereotypes proclaimed to be ruining Hip-Hop culture in the first place. In either case Black women are, and always have been, integral and resistant voices in Hip-Hop and in popular music generally. References: Bailey, M. (2013). New terms of resistance: A response to Zenzele Isoke. Souls, 15(4), 341-343. Brooks, S. (2010). Hypersexualization and the dark body: Race and inequality among black and Latina women in the exotic dance industry. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 7(2), 70-80. Brown, M. (2019). The Jezebel Speaks: Black Women’s Erotic Labor in the Digital Age (Doctoral dissertation, University of Maryland). Digital Repository at University of Maryland: College Park, MD. Duguay, S. (2019). “Running the numbers”: Modes of microcelebrity labor in queer women’s self-representation on Instagram and Vine. Social media + society, 5(4), 2056305119894002. Halliday, A. S. (2020). Twerk sumn!: theorizing Black girl epistemology in the body. Cultural Studies, 34(6), 874-891. Hill-Collins, P. (2004). Black sexual politics: African Americans, gender, and the new racism. New York City: Routledge. Miller-Young, M. (2010). Putting hypersexuality to work: Black women and illicit eroticism in pornography. Sexualities, 13(2), 219-235. Miller-Young, M. (2014). A taste for brown sugar. In A Taste for Brown Sugar. Duke University Press. Sharpley-Whiting, T. D. (2007). Pimps up, ho’s down: Hip-Hop’s hold on young black women. New York, NY: NYU Press. Stuart, F. (2020). Ballad of the bullet: Gangs, drill music, and the power of online infamy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Berkman Klein is thrilled to announce its Institute for Rebooting Social Media's inaugural cohort of Visiting Scholars—from disciplines ranging from law and philosophy to informatics and computer science. During the 2022-2023 academic year, these nine scholars will use their time with the Institute to collaborate with one another on existing work and begin new lines of inquiry.

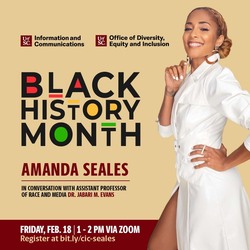

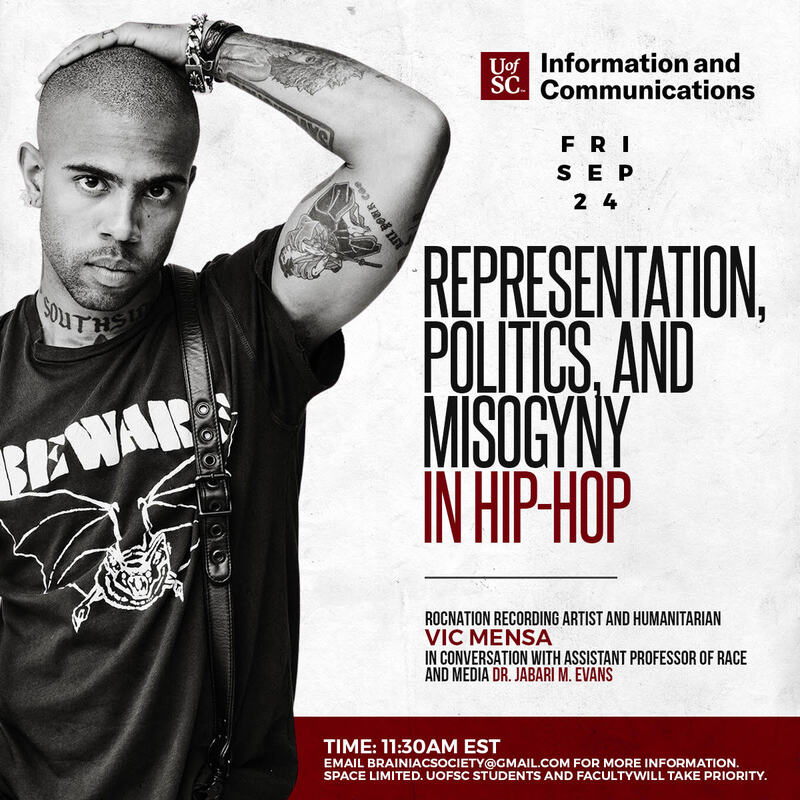

“So many of us are brainstorming what to do about the state of social media without even being in a position to well understand what it’s doing to us and where it’s headed,” said Jonathan Zittrain, co-director of the Institute for Rebooting Social Media. “This extraordinary group of scholars represents some of the best efforts to deftly apply rigorous academic thinking to complicated and fast-moving phenomena, with an eye towards interventions that help without making anything else worse.” Joanne Armitage, Ibtissam Bouachrine, Jabari Evans, Greg Gondwe, Kate Klonick, David Nemer, Yong Jin Park, Jon Penney, and Elissa Redmiles have been doing pioneering research into social media and the prospects for interventions to improve it. With the Institute, these scholars will focus on various topics, such as the decolonization of social media companies in Sub-Saharan Africa, online disinformation related to Brazil’s 2022 general elections, and digital violence against Muslim women. “We are thrilled to officially welcome our first Visiting Scholars into the Institute’s growing community,” said James Mickens, co-director of the Institute for Rebooting Social Media. “We look forward to learning with them and engaging areas of shared concern, including digital governance, freedom of speech, privacy, community-based infrastructure design, and online inequality and discrimination.” The Visiting Scholars will spend a portion of the academic year in residence at the Berkman Klein Center’s new home in the Reginald F. Lewis Law Center at Harvard Law School. In addition to their own projects, scholars will work with Harvard students, staff, and affiliates, and the broader Berkman Klein community, with the goal of producing research that is both academically rigorous and accessible to diverse audiences. The Visiting Scholars Program is part of the Institute for Rebooting Social Media’s larger portfolio of programming, research, and educational opportunities. The Program will run annually throughout the three-year duration of the Institute, strengthening the community of interdisciplinary scholars tackling the most challenging problems of social media. The Visiting Scholar selection committee included Harvard faculty Gabriella (Biella) Coleman, Nien-hê Hsieh, James Mickens, Jordi Weinstock and Jonathan Zittrain, as well as Hilary Ross and Rebecca Tabasky. The Institute and its programs are supported by generous contributions from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Reid Hoffman, and Craig Newmark Philanthropies.  This past Friday I had the honor of speaking with the multi-talented Amanda Seales on diversity, equity and inclusion within the media industries for department's Black History Month programming. The conversation was enlightening in many ways and we touched upon intersectionality on screen, all diversity not being "good diversity," the sincerity of recent public decrying of anti-blackness in Hollywood and also lastly, where her journey in entertainment is leading her presently and the near future. It wasn't recorded but the conversation allowed us to talk about ways in which inequities suffered by Black folk, both on screen and on stage, must remain in our memories if we are to adequately produce equitable futures for Black people in media. I'm happy that Recording Artist Vic Mensa will visit my Minorities, Women and the Media course on September 24th, 2021. We will discuss his life in music but also get his views on misogyny and representation of Blackness in Hip-Hop.

|

AuthorRaised on the East side of Chicago. Globally Local. Cheers! Archives

January 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed